https://www.exibart.com/attualita/donna-in-che-senso/

English version:

Woman, in what sense?

ACTUALITY by Carlo Settimio Battisti and Federico Sacco Beyond the body: the dialectics of being a woman between biology, submission and cultural construction

by Carlo Settimio Battisti and Federico Sacco

Ornella Mercier, Zygospore

Simone de Beauvoir stated ‚Women are made, not born‘. Luisa Muraro, on the other hand, replied the opposite: ‚Women are born, because we are all born as women, and men become them‘. This tension is not only theoretical, but profoundly existential. What does it mean to be a woman? And what does it mean to become a man in a society that still binds the body to its destiny? The dialectic between being born and becoming finds a dimension of confrontation and reflection in the paths of transition, highlighting how the concept of gender as a biological classification is now obsolete. It is no longer simply a question of male and female, but of a complex network of identities that are constructed, chosen and claimed. How can we reconcile these perspectives? Gender, writes Judith Butler in Gender Trouble, is „a performance, a repeated act“: biology is not enough to define it. Through its repetition and social construction, it shatters: Anna Fausto-Sterling’s ‚five sexes‘ multiply and become a thousand. We need a language that changes and evolves with us: the term ‚transsexual‘ seems to imply a final destination, a goal of sex. Instead, ‚transgender‘ reflects what gender really is: a fluidity of behaviour, a constant change. The term ‚trans‘ is stripped of any identity cage: it no longer belongs to any rigid classification, but flows, evolves along with the experience of those who live it.

This opens up the reflection on femininity. According to Andrea Long Chu, it is ‚the desire to be desired‘ (FEMALE), no longer a social obligation or a biological destiny. It is a will, a voluntary submission that is not synonymous with weakness, but is transformed into a form of power. What then does it mean to be men and women if these identities cannot be bound to the body? And what role does the body play in defining masculinity and femininity? These questions lead us to confront the conflict between what we believe to be natural and what is the product of centuries of narratives, roles and social expectations. The feminine, historically represented by characteristics of care and passivity, conceals a process of limitation. The idea that women are naturally inclined to care is nothing more than a social trap, preventing them from exploring other possibilities. Reducing female identity to motherhood is a way of confining women to a narrow space, that of mother, excluding their potential. On the contrary, becoming a man means entering a system of power based on performance and control, which not only represses other expressions, but also creates a hierarchy between genders. The masculine is associated with dominance, the feminine with submission, with limiting effects on both sexes. Ornella Mercier, Zygospore

The link between gender and social roles is particularly evident in the provocation by Deborah Giovanati, Municipal Councillor of the City of Milan, who stirred up controversy in the courtroom last October by asking the Milanese city council: ‚How do we define what a woman is? Can you distinguish who is a man and who is a woman?‘ The problem is primarily linguistic. We have associated a signifier (woman) with a fixed meaning, linked to rigid images and concepts. Giovanati insists: ‚For me, the only certainty is that a mother is a woman‘, giving in to the confusion and uncertainties of this century, probably making herself the spokesperson for a patriarchal upbringing by associating motherhood with a figure rather than a concept. It forgets, perhaps ignores, other types of parenting that cannot be associated with a biological destiny or identity. Adrienne Rich has described motherhood as one of the most powerful ideological constructions of patriarchy (Of Woman Born). However, it can be rewritten and reworked. Motherhood, traditionally seen as the pinnacle of femininity, can become a symbol of subjugation. Manon Garcia, in Submissive Is Not Born, It Is Become, states that submission is not a natural condition, but a choice conditioned by society. Women have been brought up to be submissive, and have learned to see renunciation as a virtue. But Garcia reminds us that submission can be rejected, reinterpreted as an act of autonomy. In this sense, motherhood itself, while being a form of submission, can be subverted. The link between motherhood and submission extends to the sexual sphere. Andrea Long Chu invites us to consider submission as a form of desire: desire to be accepted, to be seen, desire for relationship. In this context, motherhood becomes a form of both sexual and social submission, a voluntary acceptance of an imposed role. Chu offers us a different perspective: submission is not weakness, but power. A surrender that, through desire, generates a new form of freedom.

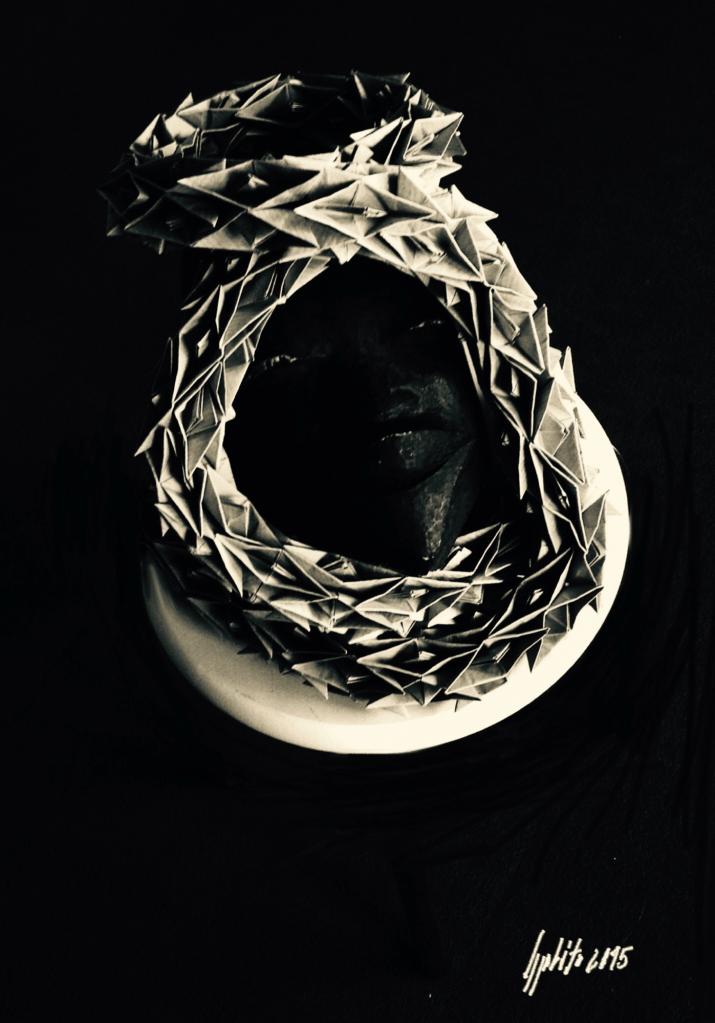

Ornella Mercier, Asebeia

At this point, the circle closes. What does it mean, then, to become a woman or a man? It means, perhaps, rejecting imposed narratives and choosing one’s own. Gender is not a destiny traced in the body, but a map that we can rewrite. Becoming a woman, as de Beauvoir suggests, is a continuous process of discovery and creation. An act of rebellion against society’s rigid definitions. In this continuous negotiation with the world, submission is transformed from condemnation into an act of freedom. To become a woman or a man, after all, is to rewrite oneself beyond appearances and imposed roles; especially if it is someone who does not look like a woman (or man) through a social lens.

This article appeared in issue 126 of exibart.onpaper.